by Andy Collins

College of Exploration Jan 29, 2005 Virtual Teacher Workshop

Andy Collins , Education Coordinator, NOAA/NOS Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef

Ecosystem Reserve

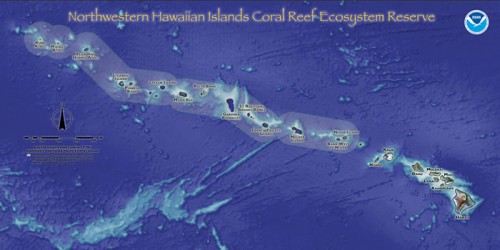

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (Reserve) is the second largest marine protected area in the world, after the well-known Great Barrier Reef of Australia. The Reserve spans 1200 nautical miles of the Pacific Ocean, and is 100 nautical miles wide for its length, comprising an astounding 132,000 square miles of area. It is the single largest protected area ever created by the United States. The Reserve was created by presidential Executive Order (EO) in 2000 in order to “ensure the comprehensive, strong, and lasting protection of the coral reef ecosystem and related marine resources and species (resources) of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.” (E.O. 13178, Sec. 2) Visit the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve online at: http://www.hawaiireef.noaa.gov/

Yellowfin goatfish - Credit: James Watt

Coral reef at French Frigate Shoals - Credit: James Watt

This EO also provided a mandate to carry out a national marine sanctuary designation process for the area. It is this designation process that is identifying issues facing the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and what a sanctuary can and should do to address those issues.

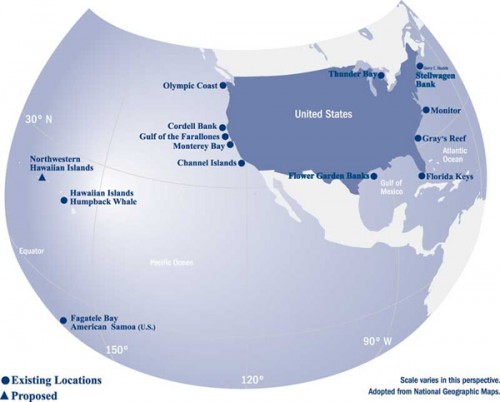

If the Reserve is designated as a sanctuary it will become the nation’s 14th national marine sanctuary, and will increase the size of the entire National Marine Sanctuary System by seven times.

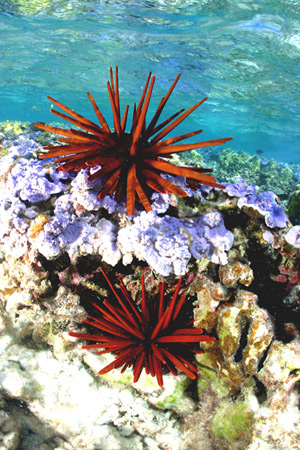

Red pencil urchin Credit: James Watt

About the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

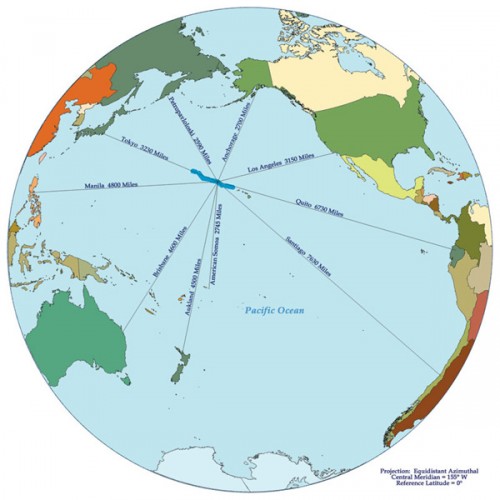

Many people are familiar with the tropical paradise that is Hawaii, a land of rainbows, giant surf, waterfalls, a living native culture, coral reefs and aloha, but most do not know that the populated islands of Hawaii – Big Island (Hawaii), Oahu, Maui, Kauai, Molokai, Lanai and Niihau – are only one quarter of the most isolated archipelago in the world. The State of Hawaii begins with the Big Island, and the southernmost point in the U.S., South Point, and extends 1600 miles to the Northwest, ending at Kure Atoll. Seen from space this string of islands, atolls and deep-water banks appear as turquoise stepping-stones across a vast, empty and dark blue Pacific Ocean.

Credit: NOAA

Credit: NOAA

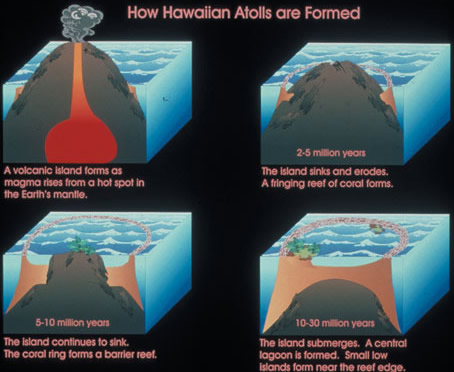

Beyond the last populated island of Niihau, called the Forbidden Isle because only Native Hawaiians are allowed to live and visit there, a chain of small basalt islands, atolls, banks, seamounts, and sandy islets stretch northwest into the vast Pacific. These tiny remnants of ancient volcanoes represent a 30 million year history of volcanic activity and tectonic plate movement. A volcanic hot spot in the earth’s crust, currently south and east of the Big Island, formed the Hawaiian Archipelago, and it has been oozing magma, or molten rock, for at least 80 million years. Kure Atoll, the last emergent land in the archipelago, is roughly 1600 miles from the hot spot, but 28 million years ago it was directly over it. As the volcanoes get carried away from the hot spot, at roughly three inches per year, they begin to erode, and collapse back into the sea.

Atoll formation - Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

All that remains of Kure’s ancient volcano is more than five hundred feet beneath the surface of the ocean, and what rises above the waves is a “cap” of coral skeletons more than five hundred feet thick, representing millions of years of coral growth. Since the Pacific Plate, upon which the archipelago sits, is drifting to the Northwest the islands are progressively carried into cooler waters until the water gets so cool that coral growth slows, and is no longer able to keep pace with the extinguished volcano sinking and eroding beneath it. Beyond Kure lie the drowned remnants of the Hawaiian chain, the Emperor Seamounts, stretching all the way to the North Pacific Aleutian Trench, near the Kamchatka peninsula, Russia. As old islands drown, new ones arise, and directly over the hot spot, a new Hawaiian island, Loihi is forming. It is currently three thousand feet below the surface of the ocean and is expected to rise above the waves in 10,000 years, give or take a few.

More resources:

See Flash clip from Mokupapapa – Isle Formation flash file

(Note: In order to get the animation to move, you will need to right click with your mouse and hit “play” in the menu. For macintosh users, that is a ctrl-click.)

Book: Kauai’s Geologic History, A Simplified Guide, Chuck Blay and Robert Siemers

Activity: Life of an Island:

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/teachers/lesson_life_of_an_island.php

The tiny islands, atolls and shoals, that compose the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) span more than 1,200 miles. If they were laid atop the continental United States, the NWHI would cover a distance equal to that between Dallas, Texas and Las Vegas, Nevada, or for you Easterners, from Washington D.C. to Fargo, North Dakota.

With their fringes of truly wild coral reefs the NWHI remind us of our past—when coral reefs and sea life across the planet thrived—a time before humans became top predator in the ocean food chain. In some ways this area is lost in time. While most coral reefs around the planet are in decline, and suffering from human population pressures such as siltation from soil and agricultural run off, accelerated alien species introductions, destructive fishing practices, and development, the reefs of the NWHI remain relatively undisturbed. Although the NWHI are not strangers to human impacts, their remoteness, paucity of habitable space and fresh water, lack of good ports, harsh winter weather, and early federal protections have mostly spared them from chronic human impacts. Today the islands and atolls of the NWHI are mostly uninhabited, only the islands of Midway, Tern Island in French Frigate Shoals, and Laysan Island have year-round inhabitants. Tern island hosts a small biological research station, Midway is a National Wildlife Refuge that also has an emergency landing airport, and Laysan has a small field camp, all are operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. A field station at Kure Atoll is owned and operated by the State of Hawaii. Several other islands have seasonal camps, mostly to monitor monk seals. In all, less than 100 people occupy all the islands at any one time.

The living coral reef colonies of the NWHI are a spectacular underwater landscape composing the majority (50-70%) of coral reefs in the United States. These reefs are some of the healthiest and most undisturbed coral reefs remaining and comprise possibly the last large-scale, predator-dominated coral reef ecosystem on the planet. The NWHI coral reefs are the foundation of an ecosystem that hosts more than 7,000 species, including marine mammals, fishes, sea turtles, birds, and invertebrates.

Endangered Hawaiian monk seal at Kure Atoll, only 1400 monk seals remain in the wild.

Ninety percent of threatened Hawaiian green sea turtles nest at French Frigate Shoals in the NWHI

The land areas of the NWHI are resting and nesting areas for over 14 million seabirds.

Shallow water coral reefs at French Frigate Shoals.

All 4 photos above – Credit: James Watt

Many species are rare, threatened, or endangered. At least one quarter are endemic, found nowhere else on Earth. Due to the archipelago’s remoteness Hawaii has one of the highest rates of endemism on earth. Many more species remain unidentified or even unknown to science. Unexplored deep-sea habitats, expensive and challenging to survey, may provide new species records to science for decades. Even the shallow coral reef habitats hold new species to science. This is especially true for invertebrates and algae.

This alga, Acrosymphyton brainardii, is known only from the reefs at French Frigate Shoals. Credit: Peter Vroom

http://noaa.stage.webthink.com/onms/Park/Parks/SpeciesCard.aspx?pID=12&refID=5&CreatureID=1278

Many new species from the NWHI are yet to be described, like this shrimp found on Midway Atoll.

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/research/NOWRAMP2002/features/shrimp.php

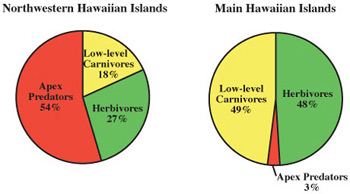

The abundance of top predators in the coral reef ecosystems of the NWHI is one of the primary factors that makes this area so unique and worthy of protection. These top level, or apex, predators are usually the species targeted by fishermen and have been heavily depleted in almost all marine ecosystems around the world. Recent science articles have decried the loss of sharks, and other large predators in the Atlantic Ocean, and it is well known that these species have suffered similar fates in other oceans. In the NWHI these apex predators are sharks, jacks and groupers and in some habitats they comprise a whopping 54% of all fish biomass. The closest comparison to NWHI reefs are the coral reefs around the main Hawaiian Islands where similar habitats have apex predator biomass, as a percentage of all fish biomass, of only 3%.

Credit: adapted from Gulko and Maragos, Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

link: http://www.hawaiiatolls.org/research/NOWRAMP_2000.pdf

Galapagos sharks, Carcharhinus galapagensis at Maro Reef.

Hawaiian grouper, Epinephelus quernus

Giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis , or Ulua.

Above 3 photos – Credit: James Watt

Hawaii’s Sharks, http://www.hawaii.gov/dlnr/dar/sharks/

Article in National Geographic Magazine about

declines in ocean predators:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/05/0515_030515_fishdecline.html

Apex predators serve an important role in ecosystems by regulating the balance of prey species, and keeping their populations in check. A reduction in predators may mean an increase in certain prey species, like algae eating herbivores, and as certain herbivore populations increase they may reduce the amount of algae available for other species, ultimately throwing the whole food web out of balance. With a healthy abundance of apex predators the NWHI is one of the last areas in the world where the dynamics of a coral reef in its natural state can be studied, and knowledge gleaned from this research will help scientists to understand what is needed to restore coral reef ecosystems that have been degraded. The NWHI can help to provide a baseline of what a healthy coral reef ecosystem looks like without human impacts.

Link: A Predator Dominated Ecosystem: Comparing the Fish of the Northwestern and Main Hawaiian Islands:

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/research/NWHIRAMP2004/features/predator-dominated.php

Stone spires dot the spine of Mokumanamana (left). Credit: Andy Collins

Beyond biological significance, the NWHI boasts a rich cultural history. During their Trans-Pacific voyages, ancient Polynesians sailed these waters and used these islands for centuries as places of residence and worship.

It is known that Native Hawaiians inhabited the first island in the NWHI, Nihoa, for at least 700 years, mysteriously abandoning the island before Westerners came to Hawaii. They left behind lava rock house foundations, agricultural terraces where they grew sweet potatoes, religious shrines, burial caves and other archaeological sites.

On the second island in the chain, Mokumanamana, 33 shrines, or marae dot the spine of the island, the purpose of which is still unknown. It is theorized that these shrines may have been used for navigational training since the island lies very near the Tropic of Cancer, or they may have been for ceremonial purposes.

The Polynesian voyaging canoe Hokule'a visits the NWHI. Credit: Monte Costa

Stone figures left behind on Nihoa. Credit: Bishop Museum,

More info:

Link: Mokumanamana:

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/about/mokumanamana.php

Archaeology of Nihoa and Necker Islands by Kenneth P. Emory, Bishop museum online cultural database

Bishop Museum NWHI Cultural Collection Database:

http://www2.bishopmuseum.org/nwhiobjects/index.asp

Polynesian Navigation

Polynesian Voyaging Society: http://pvs-hawaii.org/index.html

Book: We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific – David Lewis

Entrepreneurs tried to make a living from natural resources found there, by mining bird guano for fertilizer and harvesting seabird feathers on Laysan Island for the millinery trade. They also harvested black-lipped pearl oysters at Pearl and Hermes Atoll to commercial extinction.

In 1903 the world’s first global communications network linked through these islands. During World War II the US military developed Midway into a naval air station and submarine base, and the definitive battle of the conflict (Battle of Midway 1942) occurred in adjacent waters.

More Info: Dr. Robert Ballard discovers the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S Yorktown, sunk at the Battle of Midway:

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/midway/

Book: Isles of Refuge , Mark Rauzon, This is an excellent historical and biological overview of the NWHI).

U.S. Navy Website Battle of Midway.

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/midway/midway.htm

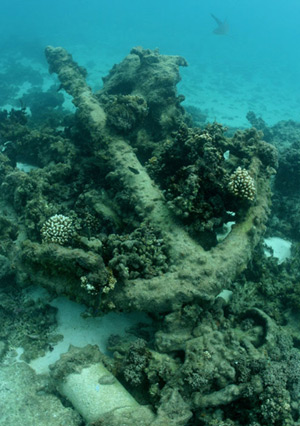

The NWHI has a rich maritime history as well, and many vessels still remain. There are 52 identified ship losses in the NWHI, and at least 67 naval aircraft crash sites. Several of the islands and atolls are named after wrecks, or captains who wrecked on the dangerous and uncharted reefs. Pearl and Hermes Atoll was named after two English whaling ships, the Pearl and the Hermes, that wrecked on the reefs during a storm in 1822. Lisianski Island was named after a Russian sea captain who ran aground there in 1805. Wrecks among the scattered islands and atolls range from whaling vessels to navy ships to Pacific copra schooners, transpacific colliers, Japanese junks and sampans, fishing boats and tankers. Many aircraft in the region were shot down during the fierce aerial combat which took place over Midway Atoll during June 1942. Like their surrounding reefs, sheer distance has served to protect these older sites, and many of them are untouched time capsules of past tragic events.

Anchor from the 19th century whalings ship Parker at Kure Atoll.

Wreck sites at Kure Atoll explored during the 2002 expedition.

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/research/NOWRAMP2002/journals/kurewrecks.php

Link to NWHI Maritime Archaeology pages:

http://www.hawaiireef.noaa.gov/research/ma/

Link to newapaper article about the 2004 discovery of an 19th century vessel at Pearl and Hermes, possibly the whalers Pearl and the Hermes

http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2004/Sep/30/ln/ln05a.html

Credit: Ocean Futures Society

Despite the remoteness of the NWHI and the minimal human population there are still threats to the fragile marine ecosystems. The most dramatic evidence of any human impacts in the area are the hundreds of tons of marine debris that these shallow reefs sift from the swirling North Pacific currents. This debris arrives in the form of trawl fishing nets, cargo nets, and a kaleidoscopic soup of domestic plastics carried here from North Pacific rim communities and fishing fleets.

This colorful collection of plastic toys was removed from the shores of Laysan Island. Over 450 tons of marine debris have been removed from the NWHI since 1997.

Activity: Marine Debris

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/teachers/lesson_marine_debris.php

Link: NWHI Marine Debris Removal Program

http://www.pifsc.noaa.gov/crd/marine_debris.html

The large and heavy nets entangle and drown marine life, and when they are pushed into shallow areas by wave energy they act as wrecking balls, abrading and breaking fragile corals. Other threats include overfishing, accelerated alien species introductions, vessel groundings, climate change, and human disturbance to threatened and endangered species.

In recognition of the spectacular natural and cultural resources, as well as maritime history of the area, President Clinton passed Executive Order 13178 that created the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.The Reserve is intended to provide additional protections to those existing in the area, and to provide a coordinating body to minimize impact among all the existing and potential uses with the ultimate goal of providing long-term protection to the region.

A short history of Federal protections in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

The NWHI first received federal protection when President Theodore Roosevelt created the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation in 1909. The reservation was created to protect the millions of seabirds that nest on the islands. Prior to 1909 albatross eggs and feathers were harvested by the ton, the eggs were pickled, and albumin from the eggs was also used for the film industry. The feathers were used for the millinery trade, mostly in Japan.

Laysan albatross eggs harvested on Laysan Island in the 1890s (Hawaii State Archives)

More info:

Link: The “King of Laysan”

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/research/NOWRAMP2002/journals/kingoflaysan.php

Video from 1923 USS Tanager Biological Expedition

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/video/tanager.php

Bird populations on the island of Laysan suffered severely from the removal of feathers, as well as from the guano mining that decimated the landscape and disturbed the nesting birds.

In time the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation became the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge, and Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1996, both refuges are under the management of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together the two refuges provide protection for all the land areas in the NWHI excluding Kure Atoll, and also protect waters to 10 fathoms around all land areas except 20 fathoms at Mokumanamana, and a larger perimeter at Midway.

Book: Excellent pre-Reserve history of the NWHI: Mark J. Rauzon’s Isles of Refuge (ISBN 0-8248-2330-3).

In 1976 the Magnusen Fishery Conservation and Management Act established U.S. jurisdiction over fishery management in the territorial waters of the U.S., defined as 3-200 Nautical Miles (NM).

In the NWHI this meant the exclusion of non-permitted foreign vessels from fishing in these waters. Prior to the passage of the act, from 1965 to 1977, Japanese longliners annually conducted as many as 2,170 vessel days in the NWHI, harvesting as much as 2,204 metric tons of tuna and 1,260 metric tons of billfish (WPRFMC 2003b). In 1991, over concerns about harmful interactions between pelagic longline fishers (mostly tuna and billfish) and endangered Hawaiian monk seals, migratory sea birds, and sea turtles, a Protected Species Zone was created by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council (WPRFMC) around the NWHI that banned these longliners from a 100 NM wide corridor running the length of the NWHI.

WPRFMC Brochure – Proteced Species Zone as PDF doc .

Hawaiian monk seal at Gardner Pinnacles. Credit: James Watt

After the exclusion of longliners from the protected species zone, later to be adopted as the boundary for the Reserve, only two federally regulated fisheries remained active in the region, the bottomfish fishery (mostly deepwater snappers and grouper) and the crustacean fishery (Hawaiian spiny lobster and slipper lobster). In 2000 the crustacean fishery in the NWHI was closed by federal court order in order to prevent lobster stocks from becoming overfished, and it has remained closed until present. There is current debate over whether the fishery competes with endangered monk seals, who also dine on the tasty crustaceans, sans melted butter.

With the establishment of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force in 1998 much needed attention was turned to U.S. coral reefs, and funding provided to increase research, education and conservation.

Hawaiian spiny lobster, Panulirus marginatus . Credit: James Watt

More info:

Link: US Coral Reef Task Force. http://www.coralreef.gov

Researchers document corals along a trasect line. Credit: James Watt

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands was identified as containing the majority of coral reefs under U.S. jurisdiction and on May 26, 2000, President Clinton directed the Secretaries of the Interior and Commerce, in cooperation with the State of Hawaii and in consultation with the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, to develop recommendations for a new, coordinated management regime to increase protection for the coral reef ecosystem of the NWHI and provide for sustainable use. Under this direction a series of visioning sessions were held to collect public comment on how best to protect the NWHI marine environment. From this input, and through passage of the National Marine Sanctuaries Amendments Act of 2000(NMSAA), the president created the Reserve through EO 13178 as amended by 13196. Both the EO and the NMSAA directed the Secretary of Commerce to initiate the process to designate the Reserve as a National Marine Sanctuary.

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary Designation

The process to designate the NWHI is being carried out in order to provide more comprehensive and coordinated protection for the area. When the Reserve was created, funding was only authorized through fiscal year 2005 (September 30, 2005) to allow time for designation to be carried out. Funding beyond this period will have to be re-authorized by Congress. As a sanctuary, the Reserve would be part of the National Marine Sanctuary Program (NMSP), which is an established program with secure funding, a well established infrastructure with over 200 employees, established education, science, research, and resource protection programs, and a network of thirteen additional sanctuaries that comprise the National Marine Sanctuary System.

Additionally, the designation process will be able to consider inclusion of State and Federal waters that are not currently in the Reserve, enabling more comprehensive and coordinated management for the area. (A sanctuary would have regulations and more robust enforcement capabilities, based on the legal authorities provided by the National Marine Sanctuaries Act.)

The Reserve, since it was established by Executive Order, can easily be amended, changed, or revoked by any future President. Changes to an approved national marine sanctuary management plan, however, require an entire new public process. Overall, a sanctuary is a more established means for marine protection, in terms of enforcement, education, research and monitoring, and funding. The designation process provides the opportunity to evaluate future management of the region while identifying the most effective methods for interagency coordination.

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Discovery Center was opened in Hilo, Hawaii in May of 2004.

Mokupapapa Discovery Center :

http://www.hawaiireef.noaa.gov/center/welcome.html

Map of National Marine Sanctuary System, NOAA

More info: NWHI Sanctuary Designation : http://hawaiireef.noaa.gov/designation/

Challenges in the Sanctuary Designation Process

Since there is relatively little human use of the NWHI many people have wondered why the designation process, and increasing protection for the area is so complex, or so difficult. Although there are many management issues that need to be addressed such as marine debris, enforcement, Native Hawaiian cultural uses, and research, two major factors complicate the designation process – disagreements over the level of fishing that should be allowed to occur in the NWHI, and the shape of sanctuary boundaries and how management will be coordinated among the agencies responsible for the area.

Fisheries management is at a turning point in its history as the regulatory agencies attempt to change from a system that bases management upon Maximum Sustained Yield (MSY) models to ecosystem-based models. One of the primary concerns of the NMSP in examining fishery impacts in the region is not only the impact to the target species but impacts upon the ecosystem as a whole. Many of the interactions between target species, particularly bottomfish, and other species are not well understood. In managing fisheries in the area the NMSP proposes an approach that favors conservative management when knowledge of multi-species, or trophic level interactions are not well studied. In general the NMSP proposes a lower level of fishing for the NWHI than is desired by the fishery management council (WPRFMC) and commercial fishing interests.

Nainoa Thompson, master navigator for Hokule'a and Dr. Beth Flint of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service converse on Mokumanamana as a Brown Booby evesdrops. Credit: Andy Collins

Hawaiian squirrelfish. Credit: James Watt

For a full background on the position of the NMSP as it relates to fishing in the NWHI see the Final NMSA 304a5 document on the Reserve’s website: http://www.hawaiireef.noaa.gov/documents/ . The Executive Summary of the document gives an excellent overview of the issue.

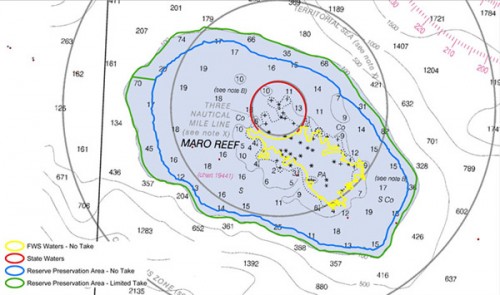

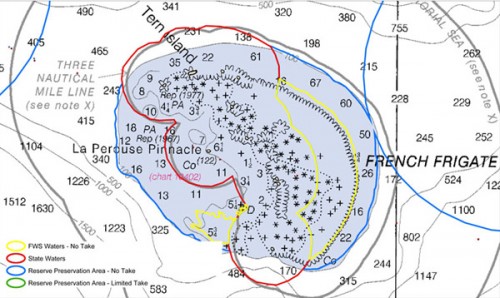

The other major issue that complicates the designation process is one of jurisdictions and boundaries and what shape the final sanctuary will take. The EO that created the Reserve directs the Secretary of Commerce to work directly with the State of Hawaii and the Department of the Interior (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), as well as other management agencies in the area to come up with a coordinated management regime that ultimately increases protections for the coral reef ecosystems of the NWHI. Three management agencies have jurisdictional authority in the area, and a few other agencies have management authority. The US FWS, through two National Wildlife Refuges (NWR), the Hawaiian Islands NWR and the Midway Atoll NWR, have responsibility for all land areas in the NWHI except Kure Atoll which is under the management of the State of Hawaii, Department of Land and Natural Resources. The State of Hawaii also has jurisdiction over all marine waters out to 3 nautical miles surrounding emergent lands. In nearshore waters, out to 10 fathoms for all areas except Midway and Kure and 20 fathoms at Mokumanamana the U.S. FWS has joint management with the State of Hawaii, and joint management with the Reserve where these depth contours extend beyond three nautical miles.

Example maps (below) from French Frigate Shoals and Maro Reef that show the complexity of boundaries between the three resource management agencies active in the NWHI: NOAA’s Reserve, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the State of Hawaii. Of course the animals don’t care about boundaries, but when it comes down to who has responsibiltiy for managing a particular area, say for a vessel grounding, or coral reef monitoring, or for the levels of protection afforded, it does matter.

Maro Reef

French Frigate Shoals

Other agencies that have management responsibilities are NOAA Fisheries, that regulates federal fisheries, and their Protected Species Division that monitors Hawaiian monk seals and sea turtles. All law enforcement for the area is currently handled by the U.S. Coast Guard. With all these agencies involved, discussions over how resources will best be allocated, and how responsibilities will be shared are inherently complex.

Also, as part of the designation process State of Hawaii waters (0 – 3 Nautical Miles), that encompass most of the shallow water coral reef habitats, will be considered for inclusion in the sanctuary. Building agreement among all these partners, while including comments from the public and advisory bodies over how best to protect the entire area, and all its resources, is time consuming and requires infinite patience.

Hawaiian monk seal resting on a sand spit. Credit: James Watt

Conclusion

The ocean wilderness of the NWHI is a special area, unique in all the world. Management of such a vast and remote marine area is fraught with challenges, particularly in the areas of enforcement and increasing our understanding of the area. It is our hope that with strong public support and participation in the process that a sanctuary designation will provide the management plan and the vision necessary to protect this special place for many generations to come.

Maps, images, and video slideshow with stunning images from NWHI

http://www.hawaiireef.noaa.gov/imagery/welcome.html

One way that we garner support is by spreading the message of marine conservation into America’s classrooms through formal and informal educators, “Navigating Change” is a project focused on raising awareness and ultimately motivating people to change their attitudes and behaviors to better care for the Hawaiian Islands and our ocean resources.

Navigating Change

http://www.hawaiianatolls.org/research/NavChange2002/index.php

Credit: Andy Collins

The project is an educational partnership that includes private organizations, state agencies and federal agencies that share a collective vision for creating a healthier future for Hawai`i and for our planet. We hope to change behaviors by creating an awareness of the ecological problems we face and by demonstrating how decisions we make in our daily lives can help resolve those problems

The goal of Navigating Change is to motivate, encourage and challenge people to take action to improve the environmental conditions in their own backyards, especially as it pertains to our coral reefs. We want people to take responsibility for the stewardship and sustainability of our islands and our ocean. We are targeting our message to the youth of Hawai`i because the future is in their hands.

To raise awareness of the environmental decline occurring in the main Hawaiian Islands, the Polynesian Voyaging Society has sailed the double hulled canoe Hokule`a throughout the main Hawaiian Islands carrying the Navigating Change message. School children and entire communities were challenged to take responsibility for our natural resources and our natural environment.

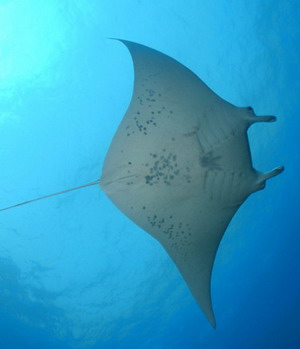

Manta ray. Credit: James Watt

Spinner dolphin. Credit James Watt

Leave a Reply